Cettire is often described (including by itself) as a drop-shipper that carries no inventory, providing it with benefits including a capital-lite model and no aged inventory risk. This is mostly true, however it does carry inventory representing goods in transit. Over the last three halves, inventory has been just under six days of COGS, which would reasonably approximate the average time to deliver to the customer, and anything that crossed over the period end would end up on the balance sheet as inventory.

This seemingly innocuous detail when synthesised with an understanding of Cettire’s otherwise standard drop-shipping model serves to unscramble the egg of Cettire’s accounts, business model and fragile margins.

Testing the counter-factual, easy as 1-2-3

It is open to Cettire to carry no inventory at all by employing a pure drop-shipping model where not only does the supplier ship the product direct to the customer, but also financially Cettire takes no ownership of the product in transit, receiving just its commission on the sale after it has been fulfilled by the supplier. So why does Cettire bother taking on any inventory at all?

There are three main identifiable differences in outcomes between Cettire’s model and a ‘pure’ drop-shipping model.

1 - Principal basis means higher revenue than agent basis

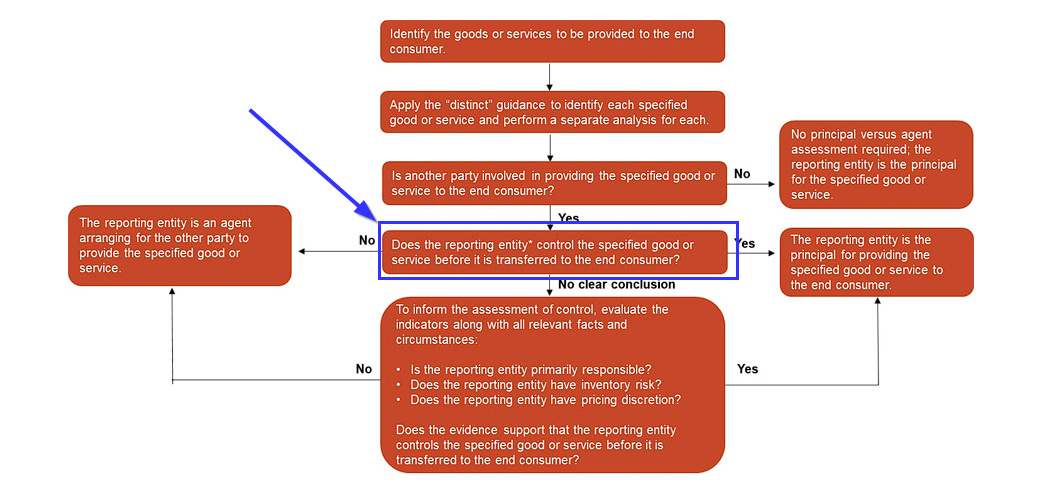

Taking ownership at the supplier’s gate ensures that Cettire is principal rather than agent on the transaction. This means the entire transaction value is CTT’s revenue, rather than just their commission, as PwC’s handy decision chart shows:

2 - Taking ownership opens up FSFE

By effectively purchasing the product at the supplier’s gate for on-shipment to the end customer, this constitutes a First Sale For Export (FSFE) which - if carefully and diligently followed through1 - means that this value ex-Cettire’s ‘commission’ is the value that can be declared at US customs.

Channel checks and various sources confirm that Cettire’s ‘commission’ is around 30% of sale value, meaning that anything sold under ~USD$1140 would escape the $800 de minimis, and items over this higher level would still benefit from reduced duty charges (to Cettire!)

This 30% commission value varies from the 35-38% product margin that Cettire last disclosed at the H1FY22 results because duties revenue is included in revenue and product margin, whereas duties cost is included in fulfillment costs and therefore is only included at the delivered margin level.

If we were to use friend of the show Ari’s 11.6% number2 for average duties on clothing imports to the US, then if Cettire was historically charging duties on the full sale price but used FSFE to declare lower prices for customs as they did with our purchase, for products in the range USD800-1140 (800/70%) this would have amounted to a benefit to Cettire of $93-132 per item which would flow straight to Cettire’s delivered margin. On Nick’s coat which attracted 16.5% duties, Cettire pocketed ~$168 of ‘duties’.

3 - Cettire takes responsibility for what information is provided to Customs

By purchasing the item at the supplier’s gate it it Cettire rather than the supplier that is responsible for providing the information for completing customs documentation for entry in to the US.

As is evident from the is-it-a-coat-or-a-jumper HS code saga documented by the AFR and in these pixels, Cettire’s track record of accuracy is in this regard is questionable at best and not-materially-but-still-significantly advantageous to Cettire at worst. In the case of the coat that ‘Jane’ bought, the advantage of the misquoted HS code to Cettire was ~$352 or 12% of the purchase price.

Synthesising margins

Once we start thinking of Cettire as a business that in general takes a commission like a standard drop-shipper, it’s clear that not only does the business model make no sense, it has never made any sense - at least not without a silent contribution from two sources - net duties revenue and net returns revenue.

The above diagram shows to scale a what the average item purchased in FY23 would have looked like if net duties revenue and net returns revenue was zero3.

Crucial to this frankly visually offensive visualisation is the yellow “everything else” part, which represents everything that is below the product margin line but above the delivered margin line. These things are:

Freight cost (including DDP fees)

Duties revenue less duties cost (net duties revenue)

Returns revenue less returns cost (net returns revenue)

Other fulfillment costs

Fitting a quart of costs into a pint pot of margin

Given that shipping cost is based on weight rather than value, that shipping an individual package weighing 500g-1kg from Italy to USA costs about EUR50/USD55, DHL’s DDP service costs about USD20 all in and that Cettire’s average order value is around USD530, it’s pretty easy to conclude that this “everything else” line is at least covered by freight costs, before we even get to the costs of managing returns.

Indeed the CFO said in the Barrenjoey-hosted duties call in March that fulfillment costs were “low double digits percentage of sales” and that freight and returns made up the vast majority of this - even including returns on a net basis since the returns fees presumably are a reduction in lost revenue rather than additive to gross revenue.

In order to reconcile this low double digits number with the 7% “everything else” which fills the gap between the 30% commission and the 23% delivered margin at the half year, we either need to flex the commission up significantly (despite a decent sample size of examples concentrated around this number) or Cettire are benefiting from a positive difference between duties revenue and duties remitted to customs. These line items seem to be the only things that can bridge the gap to the 1H2024 delivered margin in order to explain how Cettire eked out a profit during the period, precipitating the share price pop that vested the CFO’s options.

It’s a Q4 story

This analysis has been based on Cettire’s previous checkout flow that added duties at the end, as was their method until the AFR’s articles prompted a revision to duties-inclusive pricing and a returns policy that no longer required customers to forfeit duties that in at least some cases Cettire didn’t pay in the first place. Much as friend of the show and POI Julian Mulcahy justified his Cettire valuation on the basis that only FY26 numbers mattered, we can look at what these policy changes have wrought upon Cettire in 2024Q4 - before even beginning to consider the tough luxury market Cettire blame their woes upon.

Structural problem

If we take the midpoint of Cettire’s begrudgingly given guidance for delivered margin, and take 20% for the 3Q number despite them saying delivered margins were over 20%, we reach a maximum 4Q number for delivered margin of 17%., which makes Cettire broadly breakeven at the EBITDA level and unprofitable generally. Indeed Cettire have already confirmed that they are going to be taking unspecified ‘one-off’ costs below the line in FY24, so the true picture for profitability could be even worse.

By moving to a duties-inclusive checkout, this has reduced the benefit that Cettire previously gained by appearing cheaper on search engines until the checkout added ‘duties’ that were never intended to be passed through, since the calculation basis for the customer didn’t share the benefit of FSFE pricing for customs duties that Cettire enjoyed in reduced fulfillment costs. Now that Cettire bear the cost of the duties and have presumably increased displayed prices for items which attract duties, the delivered margin curve should look a lot more like the hypothetical duties passthrough scenario line below than the actual prior practice blue line, albeit that the step down no longer occurs at $800 but at ~$11404.

Explaining the profit warning - where are the promotions?

Indeed, whilst the articles that Cettire called out in its response to ASX query all mention tough demand conditions - this was supposed to be a benefit to Cettire according to POI, and eternal optimist Julian of E&P!

However even these hand-picked articles don’t back up Cettire’s assertion that there is increased promotional activity, since as our diligent readers can glean from the links below, none of these articles mention increased promotional activity.

Burberry warns of tough first-half trading as profits fall sharply

Luxury Stocks Fall as Chanel Hints at Tougher Times to Come

Cettire quietly enters China’s rocky luxury goods market

Luxury’s New Era of Uncertainty: This week, Permira pulled Golden Goose’s IPO citing uncertain market conditions, while menswear collections in Milan and Paris continued to play it safe in a softening market

Luxury goods market at a crossroads as revenues continue to slow, see muted growth

Indeed Ari’s suspicious that promotional pressure can explain the margin and sales miss:

This makes it very hard to ascribe the profit warning to the cyclical factors Cettire blamed, which leaves the structural changes Cettire was forced into after scrutiny - in sales taxes, duties and returns - mean the case is very strong that this warning was due to structural factors, and Cettire is now broken. And all it took was a little bit of daylight. How fragile is that?

Miscellany

a few other thoughts:

Shirley (Bassey) some mistake

Not many processing costs for those items where no duties were remitted Chami! If you aren’t ‘recouping’ are you just couping??

In March, Chami at Bell Potter hadn’t yet managed to synthesise that without duties, returns and all of the other bits in the Everything Else section, there’s no profit for Cettire. The 13% delivered margin in 2H22 translated to a -$14m operating loss. But perhaps she will now?

Because to me, it seems quite clear. That’s it’s all just a little bit of history repeating…

Returning to the beginning and Nick’s coat

Cettire managed to negotiate with the ASX not to give a gross revenue number or the other metrics they had asked for. This is despite it being easier to give a gross number than a net number (which they guided to in the initial profit warning), since net is equal to gross minus returns.

If we adapt the legal principle of Jones vs Dunkel to a financial equivalent, that failing to give metrics in circumstances where they easily could have done means we can infer that any metrics they could have published wouldn’t have assisted them, we might also infer that returns may have been elevated in the period.

And this despite the company’s efforts with ChatGPT fob offs! Luckily, we now know ‘chargeback’ is the magic word as Nick showed when he finally got his invoice! Much more on this in a future post…

The ‘if’ is doing a lot of work here

ok not quite because the revenue from duties add to the denominator. But I’m trying to explain this to the investors who still haven’t sold and are therefore a bit special - hey WAM, you still here?! and the 23% used here is from a smaller denominator so unlike Cettire, the errors are in favour of the argument being made. There’s a worked example lower down for those who are worried, this picture is a simplification.

Assumptions in the chart - USD prices; duties of 11.6% (as per BJ); shipping cost of $50; DDP service costing $20 used only when duties are payable at customs based on declared value; COGS of 70% of product price (pre inclusive pricing).

Isn't biggest red flag that there was no increased promotional activity that marketing to sales ratio remained largely the same as Q3 and H1?